The Film Industry in the 1960s

The 1960s marked a profound and pivotal moment in cinematic history—a decade that saw Hollywood reinvent itself amid sweeping cultural and social changes. As society broke free from rigid conventions, so too did cinema. The era brought about a shift from glossy, studio-controlled productions to grittier, more personal films that questioned authority, broke taboos, and reflected the evolving world.

Whether you’re a student of film theory, a director seeking creative inspiration, or a movie enthusiast, understanding the film industry in the 1960s is essential for recognizing how cinema came to embrace bolder narratives, more nuanced characters, and experimental styles that continue to shape modern filmmaking.

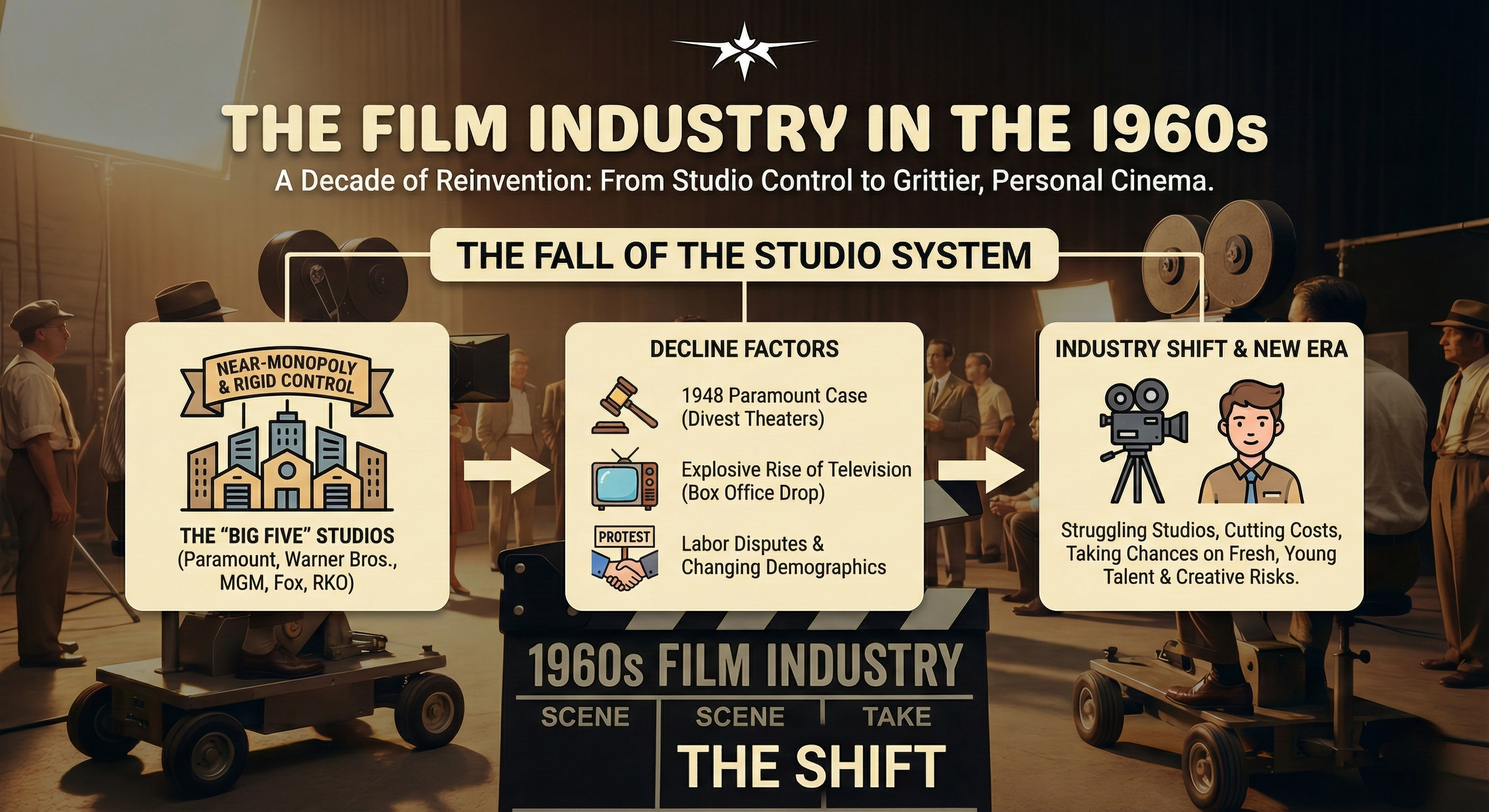

The Fall of the Studio System

At the beginning of the decade, the Hollywood studio system that had dominated for nearly half a century was in rapid decline. The “Big Five” studios—Paramount, Warner Bros., MGM, 20th Century Fox, and RKO—once held a near-monopoly over film production, distribution, and exhibition. They tightly controlled everything from casting to final edits, leaving little room for creative risks or individual voices.

However, several factors contributed to the unraveling of this once-mighty system:

- The 1948 Supreme Court case United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. had already ordered studios to divest their theater chains.

- The explosive rise of television kept audiences at home, leading to a dramatic drop in box office sales.

- Labor disputes and changing audience demographics forced studios to reconsider their rigid control.

By the early 1960s, the studios were struggling to remain relevant. They began cutting costs and taking chances on fresh, young

The Emergence of New Hollywood

Out of the rubble of the studio system rose what would later be called New Hollywood or the American New Wave. This cultural and artistic movement brought a seismic shift in how films were made and what kinds of stories were told.

A new generation of directors, many of them film school graduates, emerged with an eye for realism, personal storytelling, and experimentation. Filmmakers like:

- Arthur Penn (Bonnie and Clyde, 1967),

- Mike Nichols (The Graduate, 1967),

- Dennis Hopper (Easy Rider, 1969),

- John Schlesinger (Midnight Cowboy, 1969),

…helped usher in a cinematic revolution. Their films focused less on escapism and more on antiheroes, social alienation, and cultural unrest. This was not the polished, musical-driven Hollywood of the 1950s—this was cinema that spoke to the counterculture.

Studios, desperate to connect with younger audiences, gave these filmmakers more creative control than ever before. The gamble paid off—films like The Graduate and Bonnie and Clyde were box office hits and critical darlings, proving there was a market for edgier, more introspective cinema.

A Cinematic Reflection of Social Change

The 1960s were a time of global unrest and rapid change—civil rights protests, the Vietnam War, second-wave feminism, the sexual revolution, and growing generational divides. The film industry responded by weaving these issues directly into its narratives.

- Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) tackled interracial relationships at a time when such unions were still illegal in many states.

- In the Heat of the Night (1967) explored racism in the American South, anchored by Sidney Poitier’s commanding performance.

- Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 film Dr. Strangelove masterfully satirizes the Cold War, offering a darkly comedic portrayal of nuclear hysteria and political ineptitude.

These films weren’t just entertainment—they were cultural artifacts that captured the anxieties and aspirations of a society in flux.

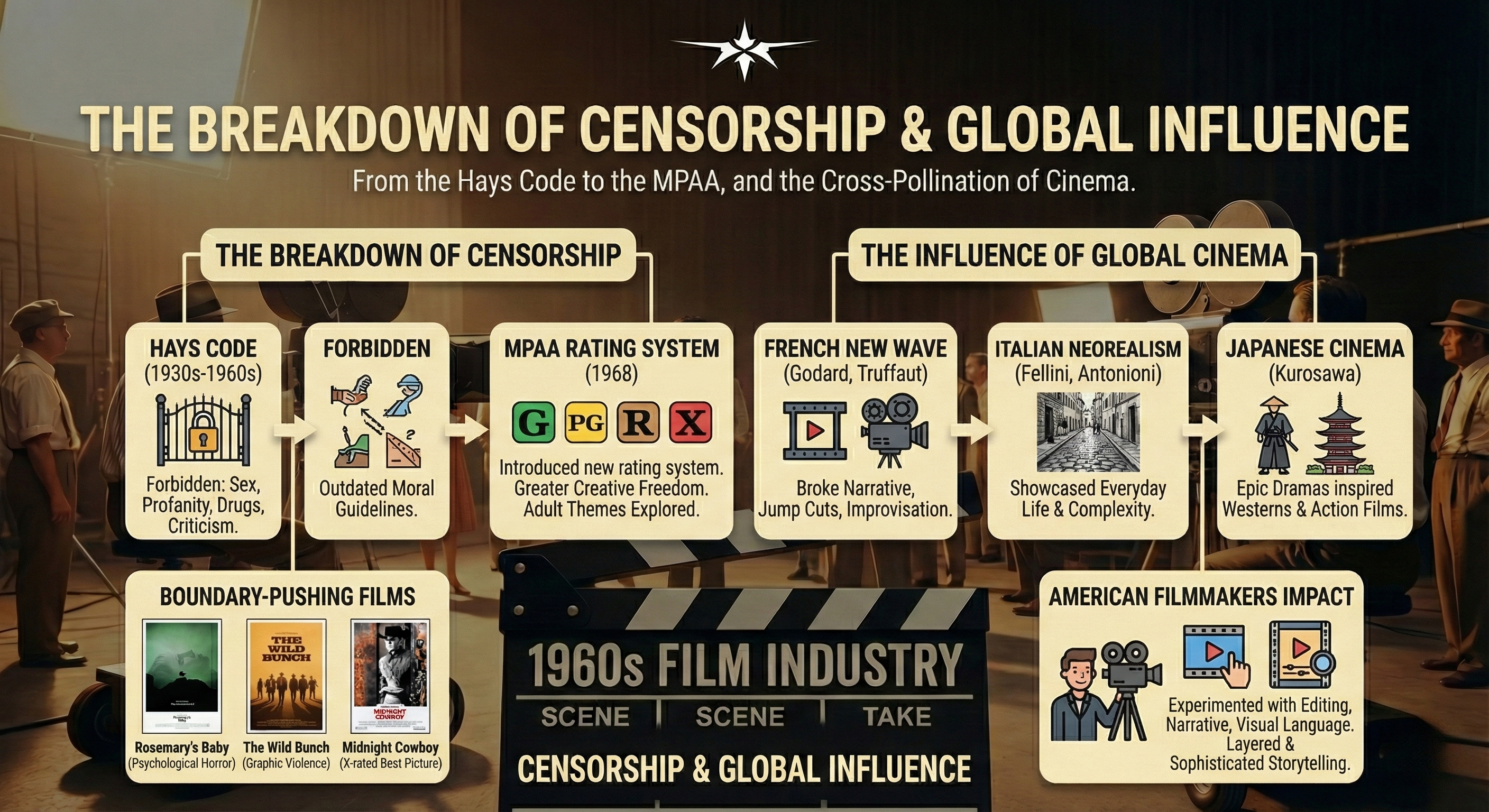

The Breakdown of Censorship

Another game-changer in the 1960s was the collapse of the Hays Code, a strict set of moral guidelines that had governed Hollywood productions since the 1930s. The Hays Code forbade explicit content, including depictions of sex, profanity, drug use, and criticism of religious institutions.

But by the mid-1960s, the code was becoming increasingly outdated. Audiences were growing more tolerant—and more curious—about grittier, more realistic portrayals of life.

In 1968, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) introduced a new film rating system (G, PG, R, X), which allowed for greater creative freedom. Filmmakers could now explore adult themes without fear of their films being outright banned.

This opened the door to boundary-pushing movies like:

- Rosemary’s Baby (1968) – A psychological horror film that blended supernatural themes with domestic realism.

- The Wild Bunch (1969) – Known for its graphic violence and morally ambiguous characters.

- Midnight Cowboy (1969) – The first X-rated film to win Best Picture at the Oscars.

The Influence of Global Cinema

While the American film industry was undergoing internal change, global cinema was also making waves. European and Asian filmmakers brought bold new ideas and techniques that deeply influenced U.S. directors.

- The French New Wave, led by Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, broke away from traditional narrative structure and embraced jump cuts, improvisation, and existential themes.

- Italian Neorealists like Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni showcased the beauty and complexity of everyday life.

- In Japan, Akira Kurosawa’s epic dramas inspired Westerns and action films alike, from The Magnificent Seven to Star Wars.

This cross-pollination of style and philosophy encouraged American filmmakers to experiment with editing, narrative pacing, and visual language, resulting in more layered and sophisticated storytelling.

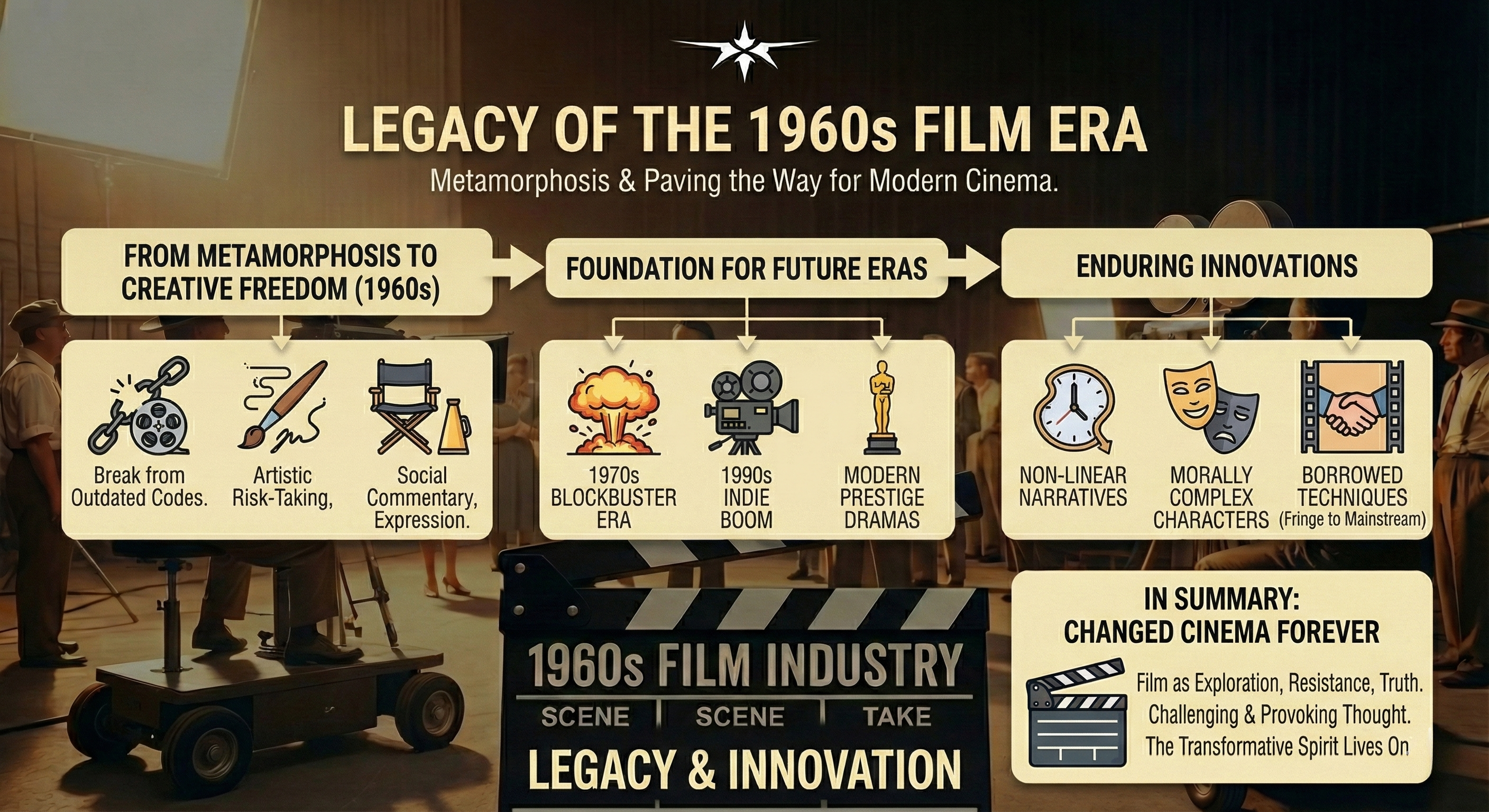

Legacy of the 1960s Film Era

By the end of the 1960s, the film industry had undergone a metamorphosis. No longer bound by outdated codes or rigid formulas, cinema was now a space for artistic risk-taking, social commentary, and personal expression.

The groundwork laid during this decade paved the way for the blockbuster era of the 1970s, the indie boom of the 1990s, and the prestige dramas and festival darlings we see today.

Many of the innovations introduced during this time—from non-linear narratives to morally complex characters—remain cornerstones of modern filmmaking. Even most commercial films now borrow techniques that were once considered fringe or radical in the 1960s.

In Summary: A Decade That Changed Cinema Forever

The 1960s were a revolutionary decade for the film industry—a period defined by the collapse of tradition and the birth of creative freedom. It was a time when film ceased to be just spectacle and became a platform for exploration, resistance, and truth.

From the raw realism of In the Heat of the Night to the psychedelic rebellion of Easy Rider, the era redefined what film could be. It wasn’t just about entertaining an audience—it was about challenging them, provoking thought, and capturing the pulse of a changing world.

So the next time you watch a film that dares to be different—visually, narratively, or thematically—remember that its boldness may just trace back to the transformative spirit of the 1960s.